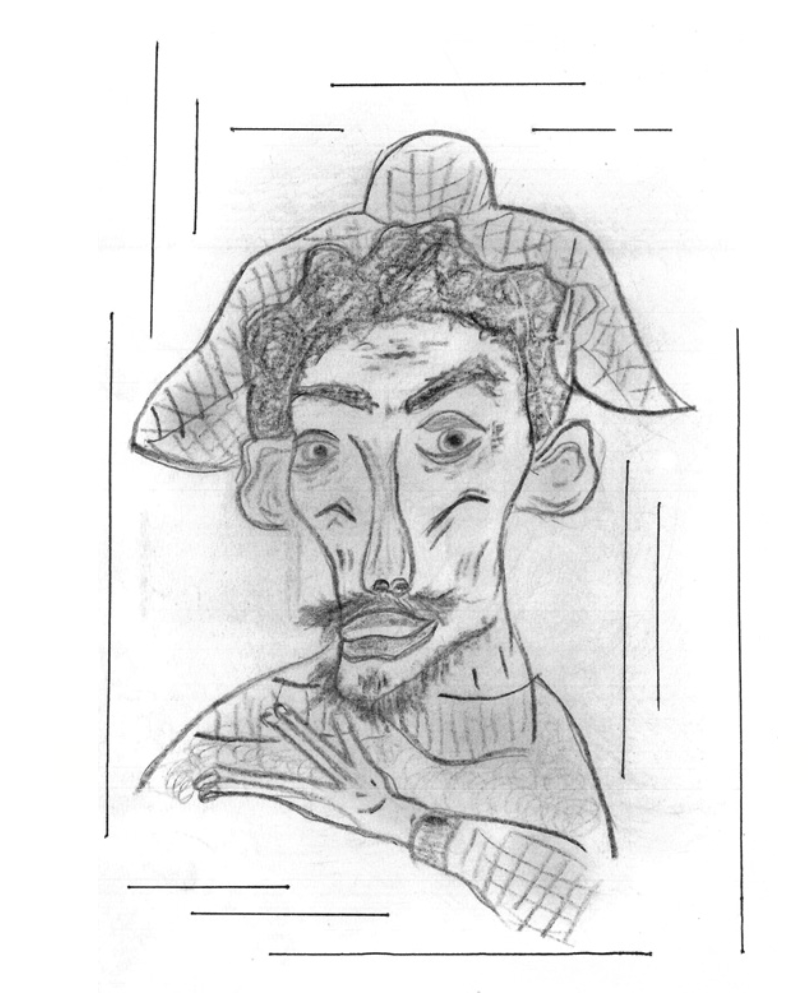

The Bandit Cinicchio

By Angelo Mazzoli

Translated/Adapted by Michelle Damiani

The city of Spello, as well as that of Assisi, lies on the southwestern slope of Monte Subasio, which belongs to the pre-Apennine mountain range. These so-called Sibillini Mountains derive their name from the Sibyl, an ancient fortune teller who lived here, in a deep cave. Sibyl could predict the future and read the signs of the past and present, so many travelers journeyed to consult with her.

Until recently, Sibyl’s cave was open to the public on the eponymous Monte Sibilla, a 2,175-meter mountainous relief located in the municipality of Montemonaco and partly in Montefortino. The area belongs respectively to the provinces of Ascoli Piceno and Fermo, and the whole territory lies within the National Park of the Sibillini Mountains.

Traveling along these paths (best with the help of a mountain guide) to la Grotta della Sibilla, or Sibyl’s cave, stirs powerful emotions. In fact, some believe Monte Subasio itself embodies the magical, the extraordinary. Its allure is such that the great poet Dante wanted to represent it in the 11th verse of Paradise in his Divine Comedy.

Even the name Subasio has mystical origins. Some believe the name refers to the God Subbazio, a pagan deity of plant life eventually assimilated into Bacchus, god of wine. Others maintain the Latin etymology derives from asio, a word that indicates a field or a large area of uncultivated land, like the ridge of Subasio, which has always been arid and left as pastureland. If the grassy dome of the mountain was called asio, the whole underlying part would be sub asio.

The larger, northern territory of Subasio belongs to the municipality of Assisi, while the southern section is located in the municipal area of Spello and has always been called Monte dei Poveri. Prehistoric populations inhabited these mountain slopes, making homes in caves that open onto the rocky terrain.

Right in the most inaccessible part of the mountain (the rocky areas of Sasso Rosso, Renaro, Gabbiano), one of Subasio’s many shallow caves lies about three meters above the ground. This natural cavity is famously known as the favorite refuge of the bandit Cinicchio, also known as Cinicchia.

His real name was Nazzareno Guglielmi, born in Assisi on January 30, 1830.

First of eight children of a farm worker named Giovanni, Cinicchio inherited his nickname from an ancestor, who was similarly short and overbearing. During Cinicchio’s childhood and early adolescence, he worked with his father in the fields before devoting himself to bricklaying. In 1854, he married Teresa, with whom he had a daughter, Maria.

His aggressive and irritable temper, combined with the widespread poverty of that time, soon led him to the life of an outlaw. In November 1857, police in Assisi imprisoned Cinicchio for theft. Apparently, Cinicchio asked permission to meet with his mother first and then, while embracing her, bit her ear, reproaching her for not educating him better. On April 20, 1859, he escaped from prison and went into hiding. Thus began the myth of the brigand Cinicchio.

It is said that his revenge could be cruel. When the gendarmes of the Papal State arrested his wife and dragged her to Perugia’s prison, Cinicchio dressed elegantly and, sitting down in a well-known café in the Umbrian capital, threatened to set fire to half the city if the police did not immediately release his wife.

Historians attribute numerous crimes between Marche and Umbria—the territory once part of the Papal State—to Cinicchio. One famed exploit actually comes from his earlier bricklaying days, when he worked on renovating Count Fiumi’s house. A laborer stole a ham from the site and the building’s owner blamed Cinicchio. For this, he was tried and sentenced to prison. But Cinicchio beat the jailer and fled, taking refuge in nearby Marche. Here he joined a band of thieves and smugglers. Jailed again in Jesi, Cinicchio tried to organize his escape but was discovered and taken to the prison of Ancona. Here he made a hole in the cell wall and, once again, escaped. He returned to Umbria and for some time sowed panic among the inhabitants of Morano, Valfabbrica, Gualdo Tadino, Nocera Umbra, and Valtopina. Probably his most notorious crime was the famous murder of Officer Cesare Bellini on October 21, 1863, at the “bridge of the cross” in Pianello.

His escapades earned him a kind of infamy, which led to this local proverb: "You have done more than Cinicchio.” Locals still use this expression to imply depravity in another, though most people don’t know its history.

But some called Cinicchio "the gentleman bandit.” Peasants and shepherds respected him, as he gave away part of the wealth he stole from the lords. Perhaps the very same lords who exploited the poor.

After he assassinated Officer Bellini, Cinicchio felt a circle closing in around him and his exploits diminished. With a fake passport, he embarked to Civitavecchia before expatriating to Buenos Aires in 1863. There he resumed his old occupation of construction.

From a letter written to his relatives we know he was still alive in 1901. After this point, we lose all trace of him. In all probability, he never returned to Italy and no locals ever saw him again. Nothing more is known about him, other than our collective memory of fables, legends, ballads, and theatrical representations.

Since the details of his life remain shrouded in mystery, his myth is being lost with the passage of time. Almost all we have left are the beautiful sentiments of poor shepherds in Gabbiano and Renaro who offered Cinicchio protection, faithful and affectionate friends until they conspired with the papal guards who relentlessly pursued him.

Then again, there is his cave on Subasio, rumored to have hidden Cinicchio away during his time as a bandit on the run. How nestled and safe Cinicchio must have felt in that tucked-away cavity, camouflaged among bushes and shrubs. Perched high in the rocks, the cave required a tall ladder to access the entrance. Once Cinicchio climbed through the small opening, he retracted the ladder.

With this legend, we see that Monte Subasio gave birth to two opposite characters. On one hand, a "saint,” Francis, and on the other a "thug,” Cinicchio. Can we then say that our mountain has two faces? That of good and holiness, that of evil and crime? In faith, as well as popular belief, the sacred and the profane often rely on the same explanations and justifications. Indeed, they are sometimes woven into the same myth. After all, a myth is nothing more than a way of telling, a way of thinking. As products of the human imagination, myths have the strength and charm to elucidate hidden aspects of reality.

Even a slight understanding of their stories reveals similarities between Francis and Cinicchio. St. Francis, emblem of Christian holiness, embraced poverty. On the slopes of Subasio, he found a warm welcome for his love for nature, drawing closer to God and all His creatures. Cinicchio, emblem of banditry, on that same mountain (though in a different cave), found a refuge from earthly justice. The pale memory of Cinicchio describes him as a fantastic, courageous guardian of oppressed people.

So we can say that for both Francis and Cinicchio, the rich hated them both, and the poor loved them both. Both figures are bringers of justice. I hasten to add that I mean the popular kind of justice, rather than that of the courts, where today, unfortunately, corruption and crime are often either overlooked or unjustly influential (oh, that wretched balance!), in their moral and social, civil, and political gravity.

“The Bandit Cinicchio ” is one story in Angelo Mazzoli’s book:

Tales from My Zia Faustina: Folklore of Old Umbria

For an electronic version of this book click here to find the book at your preferred marketplace (Amazon, Kobo, Apple, etc) or click here to buy it directly from this website.

For a print version, search for the book wherever you find your books, or ask your local library to get a copy!