Out of Italy

/A few days ago, this was my view.

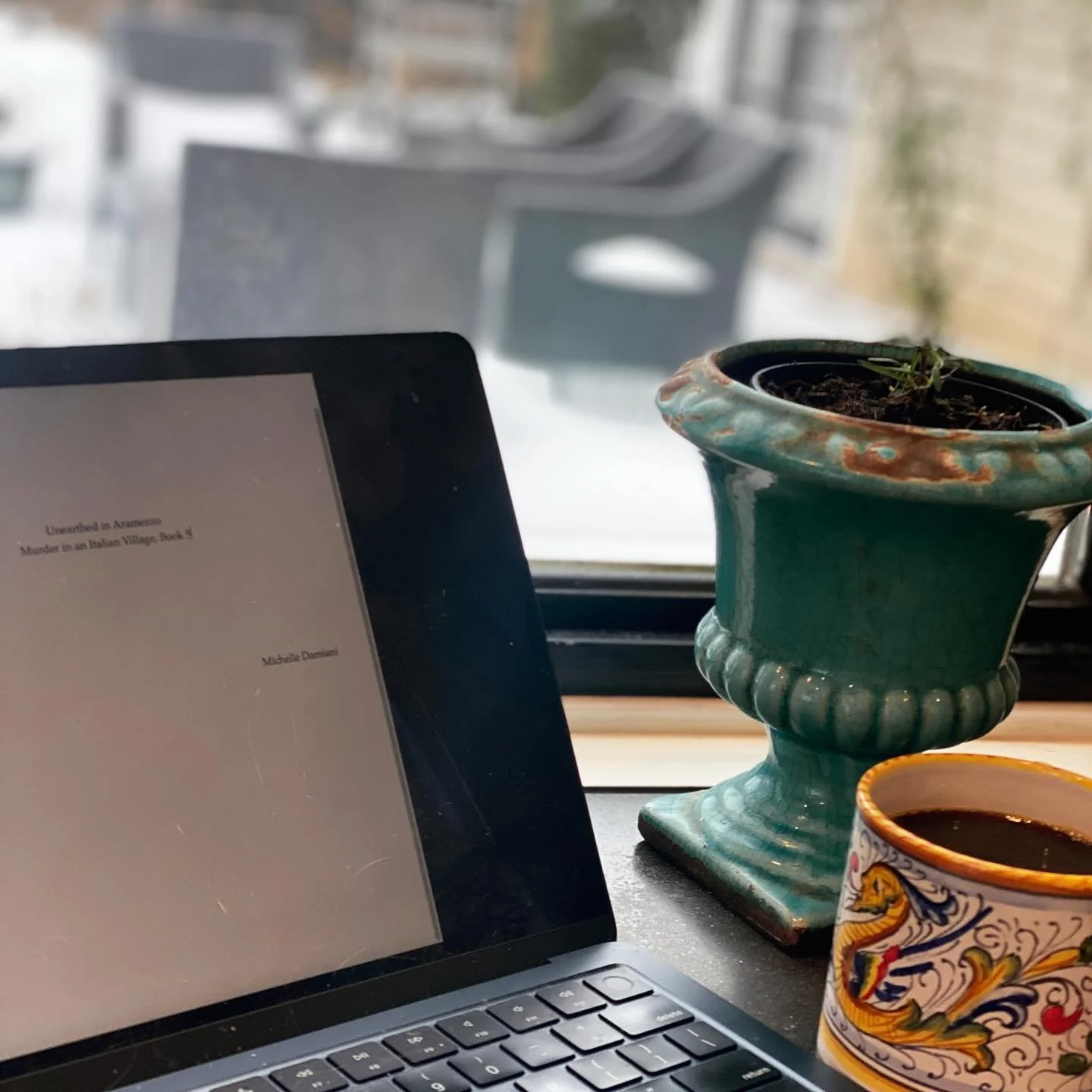

Now, this is my view.

Believe me, you are no more surprised than I am.

Especially since this story begins more than 30 years ago.

If you’ve read The Road Taken, my guide to creating an immersive family adventures abroad, you’ll remember that one of my formative travel experiences was backpacking through Europe on my own when I was in college. I wasn’t on my own the whole time, though. I spent the first two weeks with my mother and her family in Paris. Then met up with my boyfriend Keith who was studying at Oxford and we jaunted to Ireland for a few days before I launched on my own through Dublin, Lisbon, the Algarve coast of Portugal, southern Spain (mostly Barcelona), the Ligurian coast of Italy (most Cinque Terre), before meeting up with Keith again in Zurich.

How we planned any of these meet-ups without cell phones boggles my mind. But somehow I picked him up at the Zurich airport and we aimed our travels to the tiny village of Gimmelwald.

Gimmelwald is speck-sized, so it’s surprising that two college students landed there, but I had discovered the Rick Steves guides at my college bookstore and fell head-over-heels for this new travel philosophy, mostly because it made my financial constraints read like advantages. Rick Steves is a big thing now, but at the time it seemed revolutionary to consider that smaller budgets mean traveling in hostels and eating in markets, in other words, where the people are. Small budgets mean no high-rise fancy hotels that separate travelers from the very places they want to experience. By traveling on $25 a day (including lodging, but not my Eurorail pass), I’d have a real experience, not a sanitized and perfumed one. Score!

Europe through the Back Door became my bible. Back in the 1990’s, backpacking through Europe meant a lot of reading, rereading, and begging for books—what else is there to do on trains? I remember a train ride from France to Italy when a whole car realized we were all backpackers and so we did a huge book swap. The books I never parted with were Howard’s End (which I picked up in London and loved so much I essentially memorized it and wove several ideas into my thinking) and Europe through the Back Door, which, unlike other travel guides is eminently readable. Steves relays the history and connections in a conversational, immersive style and I turned pages as if it were a spy novel.

One place that Rick Steves fawns over is Gimmelwald, deep in the Berner Oberland of Switzerland. Keith had dipped his toe in the area on a high school trip, and he was all for meeting up there. So we met at Zurich airport and took a train to Interlaken. I remember sitting across from Keith on a concrete barrier by the train station, while we crunched paprika-flavored chips, and gazed over a ravine and up to impossibly tall, snow-dusted mountains. My California-girl eyes had never seen anything like it.

From Interlaken, we climbed onto a cherry-red train that chugged us up the hill to Gimmelwald. The town was exactly as charming as Rick Steves promised, but the youth hostel was full. So I sadly said goodbye to the beautiful cows with the enormous bells fastened to their necks by brightly-colored embroidered bands and we took a gondola down the mountain to Stechelberg, the village in the valley below Gimmelwald, to look for an alternative.

I didn’t consider myself as an anxious person back in college, but at that age I didn’t consider myself much of anything. Being 21 in the 1990’s meant that introspection seemed an irrelevant thing. Nonetheless, I couldn’t help but notice a twist in my gut as the gondola glided down the mountain that had nothing to do with heights.

At the time, that sudden gnawing feeling seemed perfectly reasonable. And maybe it is. Maybe anyone would grow antsy when the sun is waning over foreboding mountains and the village you hoped to find a place to sleep is suddenly revealed to be nothing more than a collection of houses.

Keith doesn’t run anxious and any anxiety he does have he does a good job of shoving away when he’s faced with my own. Good man. So as I started wringing my hands, voicing my worry that we’d have no place to stay, he grinned and said for sure something would turn up.

The gondola touched down in Stechelberg and now the collection of houses looked like a bare handful! We’d have to sleep in that field! We’d have to walk all night to a proper village!

Keith took my hand and led me down the driveway of the gondola station, murmuring soothing words that frankly began to annoy me.

Just then we saw it.

Right across the street from the gondola station, a beautiful wooden house with green shutters and a sign in the window.

Zimmer frei.

Room available.

We broke into laughter so relieved and so cosmic, I had to double over before we could make our way to knock on the door of the house that would be our Swiss home for the next week.

The stress and relief cemented the lesson that the backpacking tour was beginning to impress on my psyche, but that still hasn’t totally set—piano, piano, e tutto bene. Things may grow uncomfortable, situations may appear on the edge of teetering into a void, but one step at a time, and most problems are solvable ones.

Obviously I’d encountered problems in youth and young adulthood. My early years lacked much of the charm that defines my current ones. But travel sheds a light, and only as I trained from place to place with all my food and clothes and maps slung across my back did I begin to notice that I could have situations steeped in the odors form the abyss (to borrow a phrase from Howard’s End), but I could climb back out of them.

It’s a lesson I’m still learning. It’s a lesson it feels like I’ll always be learning. This lesson, it is my work. it’s not a trust in God, it’s a trust in the God within me that whatever happens, I’ll figure out a way to make it okay. I can get chased by drug-dealers in Lisbon or lost on a remote Italian road past dusk, and I can figure it out. Before the Zimmer Frei moment, these were hiccups, moments of fear, and then in typical adolescent fashion, I forgot all about them.

That Zimmer Frei moment, that was the first time I reconciled my anxiety with reality and decided that maybe I needed to trust that the odds of being okay outweighed the scarier image of dragging a bed of grass together to bunk down for the night. It was the first time I decided to remember.

I held fast to that Zimmer-Frei discovery as we ventured behind waterfalls without knowing what was on the other side, as we hiked up mountains with only a vague idea that food could be had in mountain huts.

I was pretty successful. Certainly, that trip made it easier to lean into the beauties of life. In that week, I savored how our laughter carried on cool, Alpine breezes, the flavor of mountain cheese on rough farm bread, and listened to the happy chatter of the glacier-fed river we walked along each day. And not to get too cliche here, but really, quite a lot of love. As Keith and I called hellos to fellow hikers in English, Spanish, Italian, French, and German while being greeted in return with all those languages and more, we had, for the first time in our one-year relationship that began in a driveway on a college trip to Pebble Beach, a sense that, like these mountains, maybe we could last.

Fast forward thirty years, Keith and I now have been married for close to a quarter-century. We’ve created and built dream after dream. We’ve shifted our days to accommodate one pandemic. We’ve called Spello home, twice. Just this year, we’ve held hands through an on-line college graduation and we’ve bopped to a funk rendition of “Pomp and Circumstance” during a drive by high school graduation. Our youngest child is about to turn fourteen and when I bemoaned having no gifts for him yesterday because no shops are open, he insisted that all he wants is snow. For this last, I blame and credit Keith in equal measure.

After all, what is the good of being together for so many years if you can’t blame your partner for whatever you find quirky and amusing in your children? Keith loves skiing and has raised our three kids to do the same. I do not love skiing, as anyone who read my memoir, Il Bel Centro, will remember. I can do the work of trusting the universe when I’m in control of my velocity, but once I’m slipping down ice, well, all bets are off. During the trip to the Dolomiti that I describe in my book, Keith lovingly urged me down a ski run beyond my level in the same supportive, annoying tones he once urged me down a gondola driveway. Eventually he asked, I’m sure in an attempt to spark reason, “What are you afraid will happen?”

Suspecting that shouting, “Leaving my children motherless!” might ring a tad melodramatic, and unable to come up with a more precise answer, I settled for a withering look.

Which, credit where credit is due, he didn’t bristle or scorn or even offer an exasperated sigh. Instead, he asked if I wanted to take off my skis and walk. “Yes!” I huffed and refused to make eye contact as he patiently snapped off my skis and hoisted them onto his own shoulder so I could make a show of storming away.

It only took a few minutes before I begrudgingly asked for my skis back. We’d hit the part of the mountain that seemed less like a death defying roller coaster and I wanted to prove something. To myself or to him or to the universe. It’s all sort of the same.

In any case, the point is—I’m not overly fond of snow. But Keith and the kids? It’s like water for fishes. They bristle at the arrival of spring’s warm breezes if they haven’t gotten their fill of snow. When February feels iced over and I start longing for the rustle of warm water, they plead for a white spring break.

Since I’m a good sport, I go along with it. Plus, I don’t mind time alone to wander Quebec City or curl on a couch and read as snowflakes fall like feathers into the whisper quiet of the mountains. Keith is always great about looking into fun things for me like dog-sledding, and now that I’ve impressed on my husband the importance of not pushing me past my limits, I do enjoy an occasional morning of skiing. As long as I’m allowed to ski only as much as I want and then go back to flop and not have to make dinner because it really takes it out of me. Even without all that, I’d support their passion because I love watching them stomp in, cheeks red and smiles radiant, full of tales of this run and another, like their speaking their own private language of reverence for the mountains.

This is all to say, the month we’d planned in the Dolomiti for our now-defunct year-around-the-world was the stop that Keith and the kids were most excited about. They so wanted to have snow all around, every day, and the ability to hit the slopes for a morning or a day on a moment’s notice.

Once the pandemic prompted our pivot to Spello, we hoped we’d still be able to get to the Dolomiti. Ever the optimist, I couldn’t imagine the virus would still be wreaking havoc a whole year after it made its debut on the world stage. That optimism, as you know, is sheer folly and totally misplaced.

Ski resorts all over Europe are shut tight this winter. Austria experimented with opening, but then threw up their collective hands. Italy keeps pushing back the date of possibly opening ski resorts. At this point, if they don’t give the go-ahead to open soon, the resorts declare the season would be too short to make it worth their while and they won’t bother.

A more immediate impediment to skiing in Italy is the pandemic related restrictions on travel. The government assigns each region to be yellow, orange, or red, depending on how well they are managing COVID. Because Umbria has done so well with the virus, we assumed we’d revert to yellow pretty quickly after the forced red and orange weeks the government imposed on the country as a whole during the Christmas holidays. After all, we’d been yellow the two weeks before Christmas (which is why we were able to hop to Venice, you can read here about how this trip changed my entire perspective on La Serenissima.)

But Umbria’s numbers are only worsening and rumors rumbled that we were slated for red status. This is all to say, the odds of getting to the Dolomiti seem vanishingly small, even if resorts open and ski regions can also get and keep yellow status (which is also not looking good).

To make matters worse, the weather in Umbria had the audacity to tilt unseasonably warm. I, of course, delight in being able to read outside, letting my eyes drift against the distant hills as they turn green practically in front of my eyes. But Keith looks like he’s about to jump out of his skin.

He researched and discovered that while Italy limits inter-regional travel, it doesn’t limit leaving the country. So we can, in fact, get to Switzerland. Switzerland itself welcomes most visitors from bordering countries without a quarantine. We won’t be so lucky on the way back, as we’ll have to either test or quarantine for 2 weeks, but that’s expected. It’s only surprising that Switzerland doesn’t have the same rule.

Now, you may have noticed that I said Switzerland welcomes “most” visitors from bordering countries. They do, actually, forbid incoming travelers from known red areas. With Umbria flirting with blushing into full-on red, we needed to leave right away if we were going to leave at all. Even though that meant arriving in Switzerland when the regulations are in full force, rather than at the end of February when they are slated to lift (I have no idea how well Switzerland keeps its promises in this regard—Italy is constantly delighting us with turning yellow before we were told that would be up for discussion or disappointing us by saying we’ll be yellow for two weeks, only to change their mind two days later and slap us with a pumpkin-colored label).

We discussed it on a family walk in the valley below Spello. The sun warmed our shoulders until we shed layers, which you know only made Keith cranky.

Siena and I agreed that it seemed… wrong, somehow, to go to another country during a pandemic. Then again, as we thought about it, I couldn’t think of why. After all, we’re moving between areas of similar contagion, and our lives will be very similar to what they are in Spello, where our only interaction with people is picking up groceries. We’d be better pandemic citizens in Switzerland actually, since we wouldn’t be stopping to talk to friends in the street or finding excuses to pop into the shop on the piazza just to see a non-Damiani. Our Swiss days would be filled with being outdoors and once in awhile picking up groceries. Safer than our trip to Venice.

I decided maybe it’s not as risky as it seems. Maybe it seems weirder than it is. But if we know we’re being careful and respecting protocols, then we can be okay with it. So Keith booked a place on Sunday and we left on Wednesday.

Here’s where it gets funny. Because of all those skiers flocking to Switzerland from bordering countries, the most likely resorts are pretty full. What with COVID, I wanted to go somewhere less amazing if that translated into fewer people. As it turns out, this was likewise necessary because those famous resorts like Zermot on the Italian border are bowl-you-over expensive. Like upwards of 80,000 Euros for a month and one was €225,000. Not to buy, remember. To rent.

So Keith looked harder and found, to his surprise, that our best option was the Berner Oberland. He showed me an apartment in our budget and laughed when he mapped it’s location relative to Stechelberg. Five kilometers.

After thirty years, we’d wind up five kilometers from that Zimmer Frei where we’d feasted on corn flakes every morning and wondered what made the milk so good (surely the Swiss cows are gloried for a reason, but to own the truth, I came down to the fact that we’d been raised on skim milk and had finally discovered a world of fat). Thirty years after we’d clasped hands and imagined a life of adventure together, we’d be bringing our children to appreciate that clattering river and those powdery peaks (well two of our children, we can’t get Nicolas here from NYC with the embargo on people coming from the States… even with his Italian citizenship, he’d have to quarantine for two weeks rendering his vacation time moot) . And we’d be there for a month. Never have we stayed in one place that long that we didn’t consider home.

Wednesday found us packing the car in Spello’s pre-dawn. As an aside: I sure love having older children who can pack and even set their own alarms and be waiting by the door while I’m still looking for the extra masks. On the drive, we listened to the third volume of a family standard, The Story of the World. How wonderful to have Jim Weiss narrate our way out of Italy and usher us into Switzerland with tales of Genghis Khan’s descendants in India and the shoguns in Japan (for the record, my favorite is volume 2: The Middle Ages… you can the CD’s on Amazon and digital downloads at The Well Trained Mind website. I credit these audiobooks for my children’s constant quest to connect historical dots and look for antecedents). As I reached in our bag for a handful of dried apples, I realized that The Story of the World is our family version of Europe Through the Back Door.

We have this family joke that the final hour of any road trip is “the curiosity hour”, where things get interesting and time passes more swiftly. For instance: “The drive to Charleston is seven hours, but that’s only six with the curiosity hour.” Some trips wind up not having a curiosity hour—my trip to check out colleges with Siena made us realize that Nashville and Memphis and Atlanta lacked buffer zone of interest. It was just tress and bam! Arrived. But this drive, we were quite sure would be so packed with interest as to earn a curiosity three hours. So the first five hours would wind us through northern Umbria, Emilia-Romagna, and around Milan. But once we hit the border just north of Milan, we’d be in Switzerland where the change of country and landscape would no doubt make the time whizz by.

We just needed to get cross that line into Switzerland. What if the border agents didn’t let us through, citing some piece of legislation we’d missed or they’d made up? What if the rules changed as we nosed our way north from Spello (this had been our concern on our way to Venice, also… what if Umbria flipped back orange and we were stopped for leaving)?

My heart rate elevated as we approached the border stop. Looking back, I think the border agent was more thrown by our clear Americanness than by people from Italy driving into Switzerland. But at the time, the amount of head shaking and eyes flitting back to where we’d come from made my breath stall in my chest. Finally, Keith said the magic words that we live in Umbria and the agent sighed in relief and asked if we had €10,000 euros in our pocket. My mind briefly flirted with the fear that perhaps we were the victims of a shakedown, but shakedowns don’t usually come with the card the border agent showed us with a cartoonish image of a handful of bills and some arcane bureaucracy speak. Ah, it’s that rule about moving money across borders. No, we did not have €10,000 on us. The border agent looked at each of us to confirm, we nodded with all seriousness. Not even Gabe was in possession of €10,000. The agent waved us through. A heartbeat later we crossed into Switzerland.

Thus commenced the curiosity three hours. It more than met expectation. Armed with Toblerone from our pit stop, we gaped as the landscape grew more and more forbidding—dizzying peaks and squat villages hunkered in the shadow of sheer cliff sides, black with melting snow. We could barely concentrate on Jim Weiss’s melodic voice spinning stories about Oliver Cromwell as we gasped and pointed at one astonishing sight after another until we arrived, exhausted and exhilarated, to our apartment on the edge of Lauterbrunnen.

After a brief respite to check out the new digs, Keith and I ducked back out to do grocery shopping. We marveled as we drove along the river, the very river we’d hiked along all those years ago, pausing to sketch and whittle. At the store we stocked up on Swiss favorites like Ovaltine (invented right here in the Berner Oberland, by a pharmacist searching for a way to decrease malnutrition. I insist this makes Ovaltine health food even when it appears in cookie form), three kinds of Alpine cheese (heady stuff after mild months of pecorino and cacciota), fondue fixings, and Ragusa (another delight from the Berner Oberland, it’s a chocolate and hazelnut mix covered with more chocolate). As my eyes alighted on a snack cake the shape of a bear, I smiled in self-satisfaction at my wisdom in reading this article on the drive about foods from the Berner Oberland. The bear got tossed in the basket with the rest of our Swiss delicacies.

With Gabe’s birthday is Sunday and no more shops are open around here than are in Spello, I wanted to buy a mug with a Swiss flag and a Swiss army knife (are they just called “army knives” here?). But the cashier told me those items were restricted and pointed out the criss cross of plastic streamers over the shelves. See, and I thought the Coop was just being festive. But no, even stores that are open are forbidden to sell “non-essentials”. My eyes lingered on the books lined up behind the tape. How can books be non-essential when ski gear is essential?

Turns out, ski gear is also non-essential and we had a really hard time buying ski goggles to replace the ones we’d accidentally left behind in Charlottesville. But renting skis is essential, you just have to rent the gear on-line and pick it up. So much for any sort of gift for Gabe. Or sprucing up our pajama and long-john game.

So I’ll take Gabe at his word that all he wants is snow, because there is a lot of that. Unless there’s a tropical twist and all this melts, he’s set.

Our first morning in Lauterbrunnen, as we walked along the river, our feet slipping out as we adjusted to walking on snow, I thought about thirty years ago. Keith and I landed in this valley almost by accident. And here we are again, almost by accident. But this time, with two of our three offspring. This glacier fed river that we can hear chattering from our porch, it’s a through line between our past and present, between our early relationship and where we are now. Between my adolescent self and my veering toward my 50’s.

Yesterday, when Keith and the kids went skiing, I decided to walk to Stechelberg. Well, that’s not quite right. I didn’t decide so much as I went for a walk and noticed a bunch of different groups heading down the road in the direction of Stechelberg in the manner of people walking to a concert, and I wondered if something was happening. Turns out, no… it was just people out enjoying the sunshine. One family stopped at a gazebo stocked with a grill and wood for picnics. I lost track of one family as I passed them, so they either turned back or stopped along the way. One woman turned off right before Stechelberg. It’s funny that people en masse can seem intentional, when really the sunshine just calls us all without our knowing it.

After almost an hour of walking, I noticed a sign that indicated that Stechelberg and Lauterbrunnen were equally distant. That’s when I decided to walk the rest of the way to Stechelberg, to see if I could find that Zimmer Frei. I felt a familiar upswell of anxiety… I didn’t really know how to get there other than following the river and I was a little hungry and I didn’t know how to catch the bus back. My footsteps faltered as my mind spooled back to that spring day all those years ago, when I learned the importance of trust. Not in anyone to take care of me, but for me to cope with uncomfortable situations. Thirty years later, I still feel the nudge of anxiety, but I suppose I’ve learned how to name it and how to temper it with reason.

I closed my eyes and remembered how to say I don’t speak German. I repeated the name of the bus stop outside my apartment until I could say it without checking. I recited the words for how to apologize. Piano, piano. I nodded to myself. Venturing into the unknown is scary, but mastering it is a rush.

Walkers passed me and for the first time, I made eye contact and said, “Guten Tag”. They smiled and said, “Bonjour.” Which became a theme. I’m not sure if there are a lot of French people in German-speaking Switzerland at the moment, or if people are assuming I’m French—Keith said he and the kids were met with nothing but French on their day skiing—but I decided I might as well speak Italian if others can speak French. The thought heartened me and I set off with new vigor toward Stechelberg.

The walk took me past farms and waterfalls and people dropping out of airplanes to parachute down to snowy fields, and always ahead of me the sky thrummed with tones of sepia. Later, I learned that a warm front from Africa not only brought the milder temperature that prompted me to remove my hat and gloves, but also laced the sky with Saharan sand. But at the time, I could only stop every two minutes to snap another photo, mystified at the sunset tones at high noon.

As we Office-fans say in my house, my dogs were barking as I arrived in Stechelberg. I spun in a circle, trying to orient my position with the river and the gondola station. I retraced those steps all those years ago, only this time with wonder rather than panic.

I found it.

The Zimmer Frei. The wood seemed more weathered but the shutters still gleamed green

I turned slowly, drinking in the mountains, the glide of glacier water over stones, the gondola dangling from a wire, and the wooden house with green shutters.

Past and present, connected by a river in Switzerland.

Please leave a comment and share this post by using the buttons below