A new perspective on Venice

/On this, my fifth trip to Venice, I discovered a whole new side of La Serenissima.

Those of you who followed my journey via social media will no doubt pipe up, “cicchetti!” and yes, it’s true that it took this many trips to discover Venice’s most budget-friendly dining option. Then again, on our first trip to Venice for our honeymoon we were too young and stupid to pay attention and after that, we always arrived with children, so the goal was less “how can we find ways to linger along a canal?” and more “how can we keep our kids from flinging off their clothes and jumping in the water?”

For cicchetti neophytes, think of them as Venice’s answer to tapas—small plates to enjoy with a glass of wine or a spritz. While you’ll find some skewers and fried balls of goodness (arancini or fried meatballs), most cicchetti trend toward “things on bread” but you’d be surprised how many different kinds of tastes you can create with that limitation (isn’t creativity heightened when you constrain an element?). So we enjoyed bread topped with greens and guanciale, decadent bloomy rinded cheese, a startlingly flavorsome sheep’s cheese with honey, baccala in many forms, and the Venetian favorite sarde in saor (sweet and sour sardines, which I almost developed a taste for). Each cicchetto runs about €1,00, which is why they make a welcome low-key alternative to expensive Venetian dining.

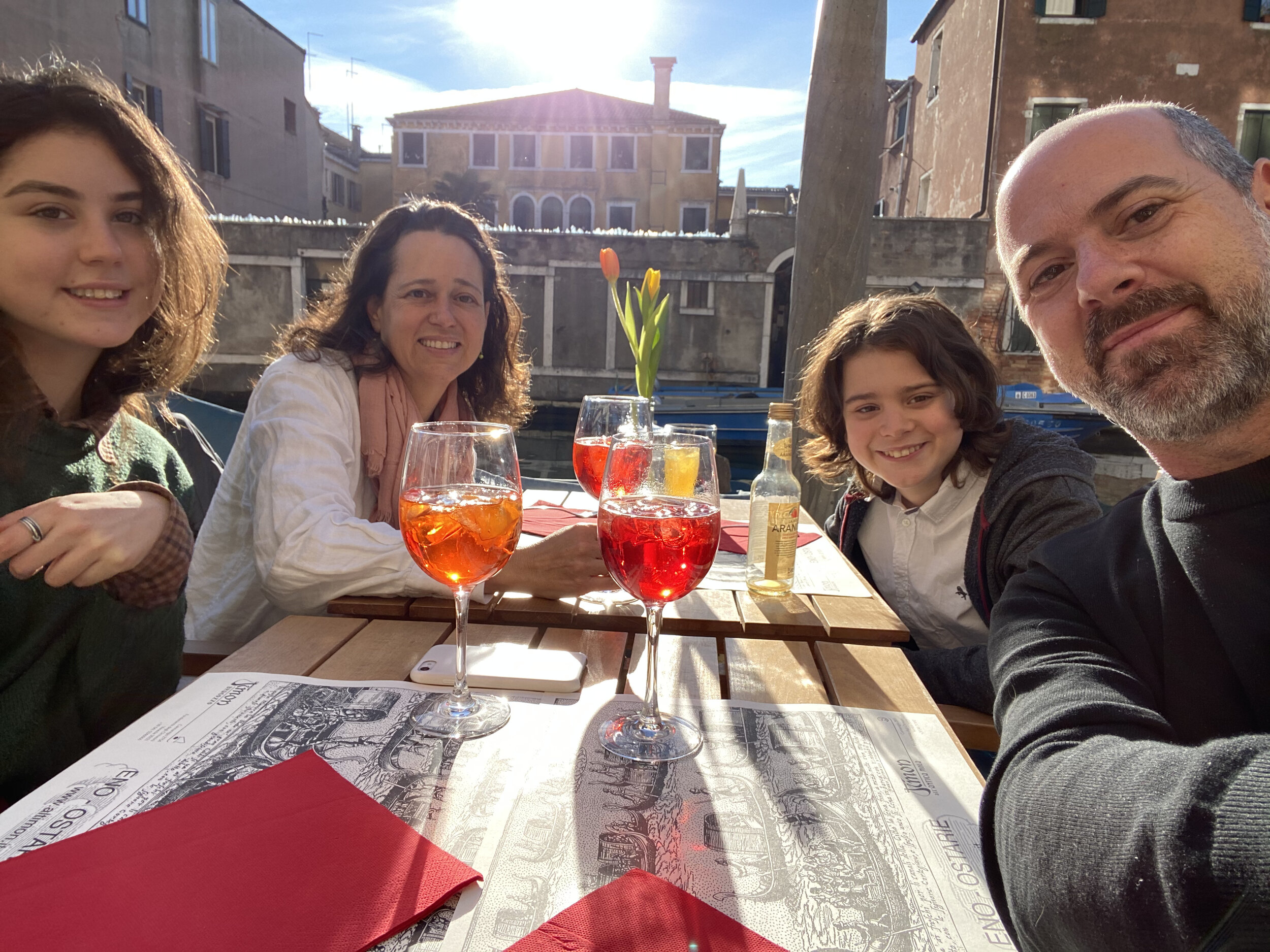

Cicchetti are common bacaro (Venice’s answer to a pub) fare, which is problematic for those of us avoiding indoor spaces at the moment. Luckily, a mild December translated to rejoicing in multiple visits to a fondamenta (imagine a canal-side sidewalk) in the Cannaregio district, lined with outdoor dining where we could nab a table and linger away a blissful hour or two moving from spritzes to wine as we sampled one cicchetto after another (you’ll find more specific information in the recommendations at the bottom).

But I digress.

And now I’m totally distracted, thinking about the blur of contentment and joy as I tipped my head back to catch the waning sun, listening to Venetians’ burbling debates as I let the flavors of my most recent cicchetto drift through me.

Okay, okay, I really am back now.

A whole new side of Venice.

When we’ve visited Venice in the past, we’ve obviously walked over as many filigreed bridges and passed as many glorious buildings as possible. We’ve ducked into churches and into museums. We’ve taken boats to islands. All of these are great ways to gain an excellent observational understanding of Venice, as if the city were a surround-sound documentary. Every trip has been lovely in that spectator-sport way, as I stood back and watched Venice unfold around me.

This, though. This was the first trip to Venice where I actually cleaved with the heartbeat of the city. Why? Because I connected to the what people do all day. To say it differently, I discovered the soul of Venice by gaining an understanding of how her people make their living, their mark, their way.

It wasn’t intentional. It’s not like I journeyed to Venice with a copy of Richard Scarry’s “What do people do all day?” tucked under my arm, eager for a view of Lowly Worm sailing a pickle boat and pigs delivering mail. Rather, the perspective began with a pandemic. You might have heard of it.

Italy has been managing the autumnal outbreak of COVID19 by mandating different rules for different regions, based on the rate of infection and the hospital capacity in those regions. Umbria has been “arancione” (orange) for much of this time, which is the middle tier between yellow (the most freedoms) and red (the least). Arancione means we can leave the house freely, but we can’t leave Spello, and bars and restaurants are closed. In December, the curve had fallen enough that many Italian regions flipped to lighter restrictions and Umbria turned yellow. Knowing that on December 20th the rules would change such that the entire country would turn red or orange depending on the day (in order to keep people from making poor pandemic choices around the holidays), we had a little time to throw together a bit of a getaway before the travel gates slammed.

We instantly thought of Venice. We visited in December eight years ago, and love winter’s foggy, quiet vibe. Spoiled by the lack of tourists on our last visit, we vowed to never, but never, visit Venice in the summer again. Plus, those spangled lights strung across streets with the rustle of canal water—it’s magic. But I worried. What would Venice be like in a pandemic December?

As I often do when I have Italy-focused questions, I hopped onto the “Traveling to Italy” Facebook page and asked if any members lived in Venice or had recently visited, and could tell me if enough grocery stores were open, if there was take-out (Italy is still under a mandate that restaurants close by 6, meaning we’d need to cook or bring in dinner), if the atmosphere was so subdued as to be depressing.

Answers poured in, all encouraging us to go—museums were closed, but many churches were still open, most restaurants were still open for lunch, we’d have no problem. Most importantly, Venetians welcomed visitors (which proved to be the case, every place we went, Venetians wanted to chat about where we came from. how long we were visiting, what we did in Spello.)

It’s funny how you can spot kindred spirits in the comments of a Facebook post, isn’t it? Something about Trisha’s response prompted me to message her and eventually that moved to What’s App. I could just tell she had that open, embracing, curious spirit that keeps me liking people.

Trisha offered me tips and resources, and in essence made the whole venture feel manageable. In chatting with her, I asked about her work and discovered that she and her husband own “VQ Travel Services”, a company that collects people from the edge of Venice where transportation ends and delivers them to their accommodations (along with other travel related services, like tours and tickets and food experiences). I leaped at the chance to request a pick-up so I’d have the opportunity to meet her. Also, it must be said, our entries into Venice are never exactly pleasant. Trying to make sense of the Vaporetto schedule, walking in circles, wondering how lost counts as lost…I never failed to arrive flustered and in need of a nap. This arrival promised to be even more bumpy, since no tourists mean the Vaporetto is running less often. We decided to skip that hassle and asked her and her husband to collect us from the parking lot.

I’m never doing it any other way.

How refreshing to exit the parking lot and spot Trisha waving, ready to guide us to the docks where we loaded our bags into their boat. Not only that, but she contacted our Airbnb host for us to let him know we’d arrived early and to ask which of the two possible unloading spots would be best for us to meet him. Her Italian, I should note, is gorgeous. Not always the case for people who have made the move to the Boot, no matter how long they’ve lived here (not a criticism of others—my Italian is crap—it was just inspiring to listen to her).

What a way to greet Venice! Trisha gave us a tour as we made our way through the canals, telling us fascinating stories. For instance, she pointed out the Riva di Biasio Vaporetto stop and said it’s named after a butcher whose sausages and stews were so renowned that people flocked from all over to line up at his shop. They lined up, that is, until a worker found a human finger in his stew. The city guards raided the butcher shop and discovered human remains. The butcher confessed to adding people to his recipes and as punishment, and his hands were chopped off and strung around his neck before he was beheaded in Piazza San Marco. Guards divided his body into four quarters which were displayed on pitchforks around Venice (I supplemented my patchy memory with information from the Venice for Kids website, which I recommend).

Trisha laughed at our open-mouthed expressions of astonishment, our eyes fixed on the Vaporetto stop. Soon, though, she regaled us with more tales, pointing out different homes on the Grand Canal, or giving insight into the construction of Venice, or offering historical insights of controversies modern and historic.

Sooner than I would have liked, we docked at our pier. Noticeably absent from our arrival was the harried and overwhelmed sensation. Rather, we arrived ready. The more so because Trisha had printed out information (helpful details I didn’t know about Venice after four visits!), and even included a map that she’d marked with important features, such as the closest grocery store to our apartment and the locations of the destinations she’d told me about ahead of time.

Part of Trisha’s services include setting up guided tours of artisanal workshops. Group tours aren’t possible during the pandemic, but she’d contacted some of the shops she works with and they’d agreed to show us in and give us an informal walk-through. Initially, I worried these would be tourist-oriented businesses—like those free boats to Murano that funnel you along like a herd of sheep through what can only loosely be considered an exhibition of glass working to dump you into in a massive gift shop where beady eyes stare until you buy something. Even without other tourists, I didn’t crave that kind of Venetian shop experience.

Luckily, that wasn’t at all what Trisha had in store for us. Instead, she pointed me to a rowing school, a studio that makes glass mosaics, and a storied velvet workshop.

The rowing school she suggested as a lark when she realized that Gabe is the same age as her daughter who rows at the school twice a week. But once she mentioned it, I cottoned on to the image like a girl to a suave gondolier. Gloria Rogliani’s school, she assured me, wasn’t one of those tourist set-ups geared toward the performance of an experience. No, this school is where Venetians send their kids to learn to row, and thus it is considerably less expensive than the tourist outfits. She encouraged me to contact the school to find out about arranging a family lesson, or sending my kids during the week of our stay. My kids were not at all interested in the latter, and I suspected they would refuse even do a family class, but I cleverly scheduled it for my birthday, when no one can fuss or complain about whatever I want to do.

As it turns out, I think they would have been game even if it without that impetus, because when we talked about what we were looking forward to about our Venice week, everyone said learning to row. Nonetheless, I loved the idea of holding that oar in my hand on my birthday. Turning 49, and thus commencing my fiftieth circuit around the sun, I thrilled to the idea of new and dazzling horizons.

I talk a good game, but I run a bit anxious. So even though I’d been excited about rowing, I woke up on my birthday with my stomach in knots. As I’ve grown older I find myself more trepidatious about novel experiences, which, let the record show, might have been an amusing side-plot if our year-around-the-world hadn’t been dashed by the pandemic. I remember when I went dogsledding in Quebec two years ago, I noticed the same pit in my gut. Hard to name—there’s nothing concrete I’m nervous about, just…embarking.

Siena, however, could name her anxiety. She looked wan from the moment she woke up, and announced she was sure she’d fall in the water. Once she said that, of course, it’s all I could imagine. One of us…all of us…tumbling into a freezing canal, cuttlefish sliding against our ankles.

I’m accustomed to my particular brand of anxiety which I’ve learned evaporates once I begin. So I simply focus on getting there and take one step at a time, refusing to let my mind spool forward into dark corners. On cue, as we arrived and got sorted, my anxiety got squished against the edge of my ribcage. We admired the school, and elbow bumped Carlo (a wonderful teddy bear of a man) and Nicolò, the student selected to translate if necessary. We piled into a boat to learn the basics of how to row and I asked Carlo, eyes dancing as I nodded to my daughter, “How often do people fall in the water?” I readied my laugh of amusement when he chortled that it didn’t happen. Maybe just when people were drunk. Instead his face grew serious. “About once a week.”

Oh, no. Siena’s eyes shot daggers at me above her mask.

Keith asked, “Anybody fall in this week?”

A moment of thought. “No.”

Dang. We’d be first. I just knew it. Carlo then leaped up to show us that the trick is to not face the water. if you keep your body facing forward, then if you lose your center of gravity, you fall…into the boat. I frowned, but decided he knew what he was talking about and anyway, he didn’t seem the sort to gloss over dangers just to make us feel better.

After showing us the basic stroke, which is, for the record, NOT intuitive (you’re standing and facing forward, so if you’ve ever rowed a canoe or a kayak or pretty much anything else, rowing like a Venetian is akin to climbing backward on a bike and expecting the mechanics to be much the same), Carlo divided us into two boats. Assuming our Italian to be better than the kids’, he assigned them in the boat with Nicolò, who fluttered gracefully about the boat, while we stayed with Carlo who speaks no English. Though once in awhile he did trot out a hearty compliment that took us a few beats to understand, but never failed to warm our spirits.

My tautly wound brain flirted with the idea of alarm when Carlo and Nicolò aimed the noses of our boats down the canals. Not a life jacket in sight (those of you who have read my Santa Lucia series may well also experience a little shiver at the notion). I tried not to fixate on the fact that the only flotation assistance I could count on were the pounds I’ve been packing on since Trisha pointed us in the direction of Ponte delle Paste (once we realized we could spy from our balcony, we found any occasion to dash out for pastries). I shook my head. Focus!

We edged out of the canals and into open water, where I had to blink to check my vision. Snow-covered Alps surrounded my view of the lagoon. They must have been far in the distance, but it seemed like the water lapped right against their base.

I had only a moment of reverence, of hush, of remembering the sunrise over the canal that morning, like a spill of pink paint across a purple sky—a fall and an echo of the beauty in the natural world, before Carlo pressed an oar into my hand.

He told us that women make better rowers (his wife, the famous Gloria who started the school, is a champion and the school is filled with the pennants to prove it), because they know how to row smart, instead of muscling through it.

I’m pretty sure he gave up on that theory with me, as my oar popped out time and time again. On our tour, Trisha had told us the oarlock is precious to gondoliers, as they are made to their specifications and are hard to replace. I could see why after rowing around the lagoon, as I gradually learned how to press the oar against the oarlock in a way that maximized the power of the stroke and minimized the odds of that oar popping out of the oarlock.

All the while, I worked against the fear of just falling right out of the boat. Every time a trash boat went by (hailing Carlo, who shouted back) or a fishing boat (same deal, the man clearly knows everyone), no matter how far away, the ripples of waves felt like icebergs threatening to capsize our crew of three. Carlo showed us how to press a knee against the side of the boat for balance. Nicolò must have shown the kids the same because the next morning over coffee we had a good laugh at the sight of a bruise on the outside of each of our forward knees.

Periodically, Carlo made his way in front of me, squaring my shoulders and holding up his weathered hand for me to aim my tender one, thus keeping me from holding the oar too high. He’d move backward, forcing me to further extend my arms, resulting in a better row. Once in awhile he’d sing to get Keith and I rowing on the same beat. After about forty-five minutes, I found something resembling a stride. The stroke became meditative, pushing (not pulling!) the oar through the water neatly, slicing through the air to replunge the oar back into the water. A few times we even got on the same beat, Keith’s and my oars in tandem. But then I’d decide we were probably the best tandem rowers ever, such quick studies! Carlo was no doubt very impressed. Every time I had a moment of self-congratulation, my oar popped back out in rebuke. Such a nice reminder to stay in the moment and enjoy the rhythm, the motion. Else I’d lose my balance all over again.

We took a break when instructed, admiring the sight of the kids speeding around the lagoon in the distance. I couldn’t help my mental image of Lowly Worm in a pickle boat. That book clearly had a formational impact on me.

Carlo must have deemed our group not completely catastrophic as he directed our boats into a canal. A canal! With sides! To be fair, this wasn’t as derelict in his civic safety as it appears at first blush, since I rapidly learned that no matter how furiously Keith and I banged the water, Carlo could redirect our trajectory or speed with what seemed a simple dip of his oar. And so we were no doubt saved the embarrassment of crashing, bumper-boats style, into canal sides and other boats by our indefatigable maestro.

Physical ineptitude notwithstanding, there is a certain beauty in skimming along in a boat used by greengrocers (the kids’ boat, however, was designed for ladies), past people walking Dachshunds in sweaters along a fondamenta, past churches presiding over piazzas criss-crossed with lights, past tunnels where Venetians since time immemorial have docked their boats before climbing steps to their home above, to perhaps sip an espresso while watching our fruit boat go by.

There is no doubt that learning to row gave me new respect not only for gondoliers, but for Venice’s history as master ship-makers. Gabe’s homeschooling during the week focused on the physics of Venice (how it was built and efforts to keep it from being overtaken by water), as well as how it established itself as the Queen of the Adriatic. You can find his work on the physics of Venice here (which transformed, as many of our worldschooling projects do, into an essay with a different focus as he deep dives into new rabbit holes of curiosity). His work on Venice as an economic powerhouse culminated in a report he gave me on a walk we took one afternoon, all over the Castello district. His earlier project had been on understanding why there is such income disparity between the north and south of Italy, and we thought studying Venice would be an interesting counterpoint to his research into the causes of the south’s poverty. As we walked through new piazzas and over bridges seemingly designed by fairies, Gabe told me how Venice was once part of the Byzantine empire, and so had access to deep pockets. Venetians utilized those financial resources to develop their ship building industry, which furthered their standing in the world market, particularly with traders. Innovation and enterprise, borne of being on the intersection of east and west and also being on a trade route, and thus privy to new ideas and perspectives, kept Venice wealthy. So you see, those boats, they are critical not only to the atmosphere of Venice, but to her history and also to her people.

Being part of it, wielding the oar, standing with my eyes ahead as my arms pulled us through the water, I felt connected with the past and present and future of this city in a way I never have before.

Plus, I really earned my heaping lunch of spaghetti with clams for lunch, a dinner spread of cicchetti with a spritz in the courtyard below our apartment before the bacaro closed at 6:00, and a grand dessert of vast quantities of sweeties from Ponte della Paste (yes, again) with Prosecco that Trisha left for us at the school to celebrate our maiden voyage.

As we laughingly narrated each of our aching muscles the next morning, I watched the boats passing below our balcony with a more practiced eye and a wash of appreciation for lives lived on the water. Understanding rowers work to move people and products through the maze of canals made me understand Venice in a whole new way.

Our visit to Orsoni was much the same, if with less potential for dramatic dunkings. The casual visitor to Venice, of course, knows that the city is big on glass. You can find glass knick knacks on just about every corner. The Rialto Bridge fairly heaves with them. Spot enough identical items and you’d be forgiven for wondering if some of these shops fill their shelves with boxes from China.

Orsoni is not that. First of all, it’s located in Venice (not Murano), no boat required. Not that I mind boats, mind you (see above ode), but location is one feature that sets Orsoni apart from other Venetian glass establishments.

The story of Orsoni, however, does begin in Murano, as that’s where Angelo Orsoni was born in the mid-19th century. Like probably everyone else he knew, he made his living working in the glass factories. Unlike everyone else he knew, glass making became his passion, and he particularly honed in on the art of colored glass. Giandomenico Facchina, the famed mosaicist, discovered Orsoni and offered him a job making smalti—the glass tiles used in mosaics—at his Venetian furnace.

This Orsoni did, eventually creating a panel of colored tiles that he brought to Paris for the Great Exhibition. What good timing, the event coincided with a rise in Art Nouveau, and thus at a time when mosaics were beginning to be appreciated as more than just the signature of medieval art. Orders tumbled in, and Orsoni provided the mosaic tiles for architectural triumphs such as the Cathedral in Paris and St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. Not one to rest on his proverbial laurels, Orsoni continued to innovate, keeping him at the forefront of glass factories.

Orsoni passed the work and the passion to his son Giovanni, who oversaw the smalti creation for the spires of Sagrada Familia in Barcelona. Though work did pause during World War II, it surged forward again afterwards, when Giovanni left the shop to his son, Angelo, whose sons expanded the scope of the shop to include finished mosaics for installation. These mosaics can be found in places such as Westminster Abbey in London, the King’s Palaces in Saudi Arabia, and the Pagoda of the Grand Palace of the Royal Family in Thailand.

This is all to say that Orsoni differs from other Venetian glass manufacturers because here you’ll find not one blown glass cat. Only colored glass panels. But the use of “only” here is tongue in cheek, as Orsoni makes glass in 3,500 colors. Not only that, Orsoni uses the techniques Angelo Orsoni discovered in the 1800’s to produce 24K gold leaf mosaics, colored gold, and Venetian smalti. Smalti that come, again, in 3,500 colors. It bears repeating because that is just more colors than one can imagine.

The door to Orsoni opens into a courtyard, and when the employee who had agreed to show us around met us she confirmed that we could manage the tour in Italian. And then she was off. We barely kept up, but luckily the visuals at Orsoni speak for themselves. We saw a display of how gold is hammered into leaves, and then…well, the rest seemed proprietary (we weren’t allowed to take photos), so I won’t tell you the process, but suffice it to say, watching the glass meld with the gold leaf was so mesmerizing, we could have watched those workers move in front of the fires all day, even if we hadn’t been captivated by the cozy warmth of the furnace. I can tell you that the process includes one of Angelo Orsoni’s innovations, a rotating cylindrical press to compress the incandescent glass. This pressing of the glass into sheets is hypnotic, but more importantly to those in the industry, it produces a more even surface.

We also watched the glass snapped into cubes to fulfill orders, and best of all we wandered, awestruck, through a glass library. Warehouse sized, the room holds cubbies filled with glass panels in every one of those 3,500 colors. I particularly enjoyed the section devoted to skin tones (of all kinds) and also the section devoted to Mary, in shades of blue and rose. I also loved the “card catalogue” where artists and designers can root through squares of color, find one they like, and then flip it over where a number indicates the location of the sheet of that color glass.

Wow.

Our host led us upstairs where we witnessed mosaics in action, as an artist neared the final stages of a mosaic reproduction of one of Van Gogh’s fields of sunflowers. The mosaic artist propped a photo of the original in front of her and referenced that as she chipped pieces of glass into shape to follow the color and contours of the Van Gogh. She clearly had a flow I hesitated to interrupt with our presence, and yet, I couldn’t help but linger to watch her test colors and shapes, her eyes trained on the spot to fill, before using a tool to shape the glass. The end result eerily held some of Van Gogh’s tension, as the facets of glass mimicked the boldness of his brushstrokes.

Our final treat was entrance to a bathroom completely done in gold glass tiles. What luxury! Our host pointed out the curtains were made by Bevilacqua, and I smiled, knowing we’d be having that tour the next day. As we left, our host gave Gabe and Siena each a bag of glass tiles, which they enjoyed arranging and rearranging as we waited for lunch.

Tessitura Luigi Bevilacqua was trickier to find than Orsoni, but Venetians appear accustomed to guests arriving late because they went down the wrong blind alley, the employee who met us waved our apologies aside as she shepherded us into the ancient workshop, where our mouths fell open.

But first a bit of background. You might know that the four horses on display at San Marco’s basilica were “taken” during the siege of Constantinople in the early 1200’s. This event also resulted in silk culture arriving in Venice, and by 1265 Venice had its own Weaver’s Guild, called the Samite Weaver’s Guild to connect the guild to samite, a kind of heavy silk fabric (sometimes featuring gold threads) favored by kings with plenty of treasure in their storehouses. The guild oversaw the Venetian production of other luxury fabrics such as brocades, damasks, and satins, too.

The stage was set for the arrival of velvet in the 14th century. It came by way of Lucca (also a stop on the Silk Road) and thanks to the already thriving fine-goods weaving industry, velvet became a favorite in Venice. By the mid 1300’s, in fact, velvet weavers had their own guild. The fabric took off, and in the time between 1493 and 1554, Venice went from boasting 500 weavers to having 1200.

Thanks to the industrial revolution in the 1800’s, mass produced goods threatened cherished artisanal traditions. As new looms made weaving faster all over Europe, the old ones fell out of favor and spelled doom for Venice’s Weaver’s Guild and its famed handworked velvet.

Luckily, by the late 1800’s, interest stirred for handmade goods as an antidote to mass produced products. Luigi Bevilacqua seized this shift in tides and bought an abandoned Weaver’s School in the Castello district and founded Bevilacqua’s Weaving Mill, dedicated to preserving the craft of old-world velvets. Bevilacqua’s interest in textiles was more than just historical fascination. Roots of textiles and the Bevilacqua family go way back; in fact, one of the commissioners of a 1499 painting of “The capture of St. Mark in the synagogue” by Giovanni Mansueti was “Giacomo Bevilacqua, weaver”.

Bevilacqua recovered 18th century looms from Venice’s old Silk Guild, along with the machines to prepare the threads. All the looms are completely hand operated and therefore the fabrics take an exceedingly long time to manufacture. Weavers working in this old style produce just 30 to 40 centimeters a day. it’s extraordinarily physical work, as the weaver must push the pedals that move the punched cards (imagine how a player piano’s “cards” communicate the notes to the piano, the punched cards communicate the design to the loom), as well as pressing the pedals that move the threads of warp and weft, and the metal bars that create the fabrics pile, as well as cutting the threads along the thin rods to allow the threads to stand up and create velvet.

Years ago, Bevilacqua moved from Castello to Santa Croce. Which is where we finally found the piazza with a simple plaque next to a door reading “Luigi Bevilacqua.”

Our host ushered us through a hallway to the factory—an airy workspace lit by skylights. Wooden looms packed the space, filled also with the sound of shuttles sliding as modern women worked over the ancient warp and weft. Each ancient loom is topped by the shifting cards which determine the design (there’s a description of how this works here). Our host pointed out the wall on one end of the factory, stacked with over 3,000 ancient patterns, from Byzantine to Art Deco. Those cards are too delicate to use anymore, but they are critical for replicating historic patterns. Looms stand ready, so if a weaver isn’t working on a commissioned velvet, they produce one of the famed Venetian designs.

Watching weavers in action, it’s shocking how slow the works proceeds. For one, it’s just a slow process to do anything without a motor. But for another, the looms are fragile and break easily. When they do, weavers have to harvest pieces from other looms. Often they have to determine the problem by sound, which is why no music plays in the workroom. Weavers listen as the looms sigh and chatter. They can’t let their attention drift, even for a moment. This is full-intensity work, as well as more physical than one would assume.

I watched as a woman dragged a ladder to her loom to scamper to the top. She rustled around for some time before descending and trying the loom again. I shook my head. What laborious work. Our host told us that in another factory they have machines to produce larger orders, but even those could hardly be considered fast fashion. Here’s a video to watch the process, at the end you’ll see weavers working the looms by hand.

We walked by a design that I couldn’t photograph as it’s for a fashion label that I won’t mention in case that, also, is a secret. Our host told us that years ago a designer mentioned that the velvet brocade for his runway show came from Bevilacqua and after that designers clamored for these fabrics. We learned that designers rarely mention their fabric supplier to avoid competing for resources, so this was a departure and also makes me feel circumspect about naming the designer’s fabric. But I will say it was glorious, so look for some seriously astonishing velvet brocade on upcoming runways.

As we loitered beside looms with ongoing work, our host (who must have had millions of things to do above stairs and yet smiled so patiently as if she had all the time in the world) told us about the fabric commissioned for the Kremlin and for a castle in Sweden. I tried to imagine a room full of this velvet and just then she ushered us into the fabric room. Here, she showed us how the looms created different textures depending on if the threads were cut. I ran my hands over the luxurious fabric and immediately wanted everyone to leave so I could curl up on it.

A door on the far end of the fabric room raised my curiosity and I turned to our host. She smiled and encouraged me to open the door. I did, which is how I discovered that Bevilacqua holds an exalted position on the Grand Canal. My head swiveled fast and our host laughed, saying we were welcome to go out and enjoy the view, but please be careful as the dock can get slippery.

My toes just inches from canal waters, I watched boats making their way up and down the canal as they’ve done for centuries, with my back to a room stacked with fabrics made the same way for centuries. Fabric that no doubt once cloaked men and women making their way to a masquerade or an opening at La Fenice. This fabric…it’s, if you’ll forgive the obvious metaphor, woven into the history of Venice.

I felt quiet as I reentered the room and asked about the weavers. Ah, the host said. Velvet weaving is a dying art. Not too many people yearn to work an 18th century loom in this day and age. I remembered when Siena took fresco-painting lessons in Arezzo, how she mourned that fewer and fewer people retained the interest and the knowledge to pass along these iconic art forms. At Bevilacqua, workers trained for at least three years to learn to work the looms.

As we headed away from Bevilacqua to our wine tasting in Dorsoduro, I considered how Orsoni and Bevilacqua had offered a window into the gilded nature of Venice, the glitter of glass and the rustle of rich fabric. Venice’s glorified position on the trade route translates into the people having time to fine-tune skills to create labor-intensive textiles. As such, the glass and fabric are both an outgrowth of Venice’s rich history and also continually feed Venice’s reputation as a place to acquire the fantastic, the glittery, the wondrous. And the people that work those skills, they are therefore tied into the soul of Venice in a way I never considered.

(note to those who fancy visiting these workshops—Neither Orsoni or Beviliacqua have systems in place for tours, but you can contact Trisha for her artisans tour which includes both, plus a spritz!)

After our visit to Bevilacqua, we headed over the Grand Canal to Dorsoduro for a wine tasting with Cecllia from Taste Venice. Because of pandemic safety precautions, we couldn’t do one of her normal wine and food experiences, but she was able to set up a table at a bacaro she knows to be COVID-careful, where we could have a room to ourselves and she could seat herself at a distance while still telling us about the wines of the Veneto (for those interested, she’s doing virtual wine tastings, so please check out her website whether or not you have a trip to Venice in the cards).

I’d never done a wine tasting before, so didn’t know what to expect. But food is always my favorite entry into a culture, and therefore, a wine tasting with cicchetti pairing sounded like a necessary facet of our trip.

In my head, I imagined wine tastings as somewhat fussy affairs—a lot of plunging noses in glasses and leaning hard into poetical language to describe the ephemeral. From the moment Cecilia sat down, I knew that would not be our experience. In fact, later when we recounted which were our favorite activities in Venice, I realized aloud that none of us had mentioned our wine tasting. Siena said, “That’s because it didn’t seem like an ‘activity’. It was lunch with a friend.”

Perfectly captured. We laughed and talked and the learning bits effortlessly wove into our gasps of delight at the expertly chosen cicchetti and the beautifully paired wines. Under Cecilia’s deft direction, we tasted the minerals in the Prosecco, the pineapple in the Soave, and the leather in the Valpolicello Ripoasso. More than that, we learned how these particular wines differed from the mass produced variety, and began to appreciate the particular care grape growers and winemakers take to coax complexity into a bottle.

Venetians aren’t grape growers or wine makers, obviously. But thanks to cicchetti, we learned this trip how the bacaro is a beloved part of a Venetian’s life. So tasting the regional wines enjoyed by thirsty Venetians in every neighborhood tied our understanding of the island’s culture with those who poured wine as well as those laborers who popped into a bacaro after work for a spot of relaxation and camaraderie before heading home.

I should note here that the major accolades for our excellent wine tasting go to Cecilia and her open-hearted way of including us all (Gabe felt emboldened to ask what was the strangest description of a wine she’d ever heard. If you meet her, ask, we still talk about her answer). Part must also go to Cantina Arnaldi, which served local bloomy-rinded cheese that our Umbrian trained palettes had forgotten existed as well as a kind of prosciutto raised by the owner’s uncle, unlike any we’ve had. The atmosphere was casual and cheerful, and it attracted a wide variety of guests who even chose to sit outside on this brisk afternoon in order to share in the conviviality and excellent products. Next visit we’ll be sure to spend more time here, particularly since I very much enjoyed the workaday vibe of the Dorsoduro neighborhood. It felt like a “regular” version of Venice, with dogs ducking under bridges as their cargo-filled boats slid along canals and a broken-in feel of buildings surrounding piazzas. Here thrives a sense of community.

Speaking of community, I think this might be the biggest advantage of visiting Venice in the off season. Without the crowds, it’s easier to spot people running into each other on a bridge or outside of a pizza shop. i suddenly saw Venice as a village. It would be easy to assume the lack of tourists stemmed from the pandemic, and I’m sure that’s partly true. But honestly, Venice seemed as crowded this December as it did 8 years ago when we visited in winter.

I expect that with the pandemic, Venetians, like people everywhere, delight in running into friends and neighbors and use those out-of-door meetings as a substitute for indoor gatherings. This could be part of why we were far more aware of the joy one can see in the eyes- above-the-mask when people spotted a friend.

This is all to say, when travel opens back, please consider visiting Venice in the off-season. You’ll get the lack of crowds we enjoyed, with beauties the pandemic denied us—like the ability to dine in tucked away corners of cozy restaurants, museum interludes, not having to count the people in a bar before entering to make sure you aren’t violating regulations, and seeing people’s whole faces as they bustle to and from work.

In other words, when you visit in a non-pandemic December, you’ll get the opportunity to connect with what we could only witness. Well, that’s not strictly true. Thanks to Cecilia pointing us to restaurants and sending me updates about shifting regulations, I felt like we had a soft place to land, a personal connection.

And how marvelous to have Trisha checking in after a tour to see how we enjoyed it, to have her asking for photos from our time at her daughter’s rowing school, and to have that bottle of Prosecco and a hand-painted mask waiting for us when we returned, flushed with triumph and joy. Trisha pointed me to the fabled Bar Rizzardini, whose pastries and coffee and orange juice we loved so much we wound up there four times in seven days (later, Trisha told me that owners sent us their regards and I seriously had a fangirl moment) and to Antico Forno where we had our best pizza in years (remember: we do live in Italy, so this is saying something). Trisha was constantly available when I sent her a panicked, “wait! how do we get there?” text. I recommend checking in with her for water taxis, boat tours, and shop tour possibilities when next you come to Venice. Which I really hope is soon. Venice is looking forward to welcoming you with open arms.

This trip has changed how I travel, and what perspective I want to engage when visiting new places. Now, I get it. When you ask, “What do people do all day?” you begin to understand the residents who walk those lanes. You begin to feel a part of the culture those residents have built together.

Stay tuned for more photos (including probably the best photo of the trip) and recommendations below!

What have been your Venice highlights? Please do share this post with your friends…

Further Venice Favorites

Favorite View: The roof of Fondaco dei Tedeschi. You don’t need to pay, but if you go in a busier time, you’ll need to book your visit, via their website. It’s pretty fun to take the steps down and take a gander at all the high-end goods.

Favorite Street Food: Even though I loved where we stayed, we should probably rent an apartment in San Polo next time because it seems like we were on this one road, every day. I mean, when one thoroughfare boasts your favorite bar, pizza, and street food, it’s pretty good, right? Acqua e Mais is pretty set up for the pandemic, even in non-pandemic times, with their window that faces the street for easy pick up. We got some excellent fried seafood here, along with a new taste for me—fried mozzarella with anchovy, which is this impossibly light confection that is crispy and creamy with just a hit of savory. If I didn’t know what it was, I probably wouldn’t have been able to guess. Even if you won’t be in Venice any time soon, I encourage you to check out their menu, which is beautiful. I can tell you that picking up some boxes of Venetian street food, along with some Asian dumplings from La Ravioleria, make for a rather special last dinner in Venice, especially when the pandemic prevents you from being able to dine out.

Favorite Bookstore: Libreria Acqua Alta. This bookstore’s low position on a canal has made it vulnerable to more than its share of Venice’s famed flooding. They’ve taken those destroyed books and turned them into stairs to peek over the wall, as well as art installations. Cats abound, see how many you can find. Our favorite was curled up in the children’s section, alongside the “fire exit”, a gondola you can sit in. Great books, too… we picked up art books for Siena, a “Pimpa in Venice” books for Gabe (he’d been asking for his favorite Italian cartoon, but we hadn’t been able to find any with our closest bookstore closed), and even a deck of delightful Venetian scopa cards. We play a lot of scopa in our family, I really recommend it as a way to while away an afternoon with a glass of Prosecco. Gabe wrote up an easy-to-follow instruction sheet if that’s helpful.

Favorite Bar: As mentioned in the post, Bar Rizzardini astonished and delighted us, many times. Every pastry was divine, but as a group, we particularly adored the krapfen (the lightest donut I’ve ever had, filled with cloud-like cream), the coconut and chocolate cake, and the festivi, almond pastries available on Sundays. Don’t miss the spremuta. We spent far too much time wondering where in the world they get their oranges, as we’ve only had orange juice like this before on Ischia, in the Bay of Naples. If anyone knows, tells me!

Favorite Walk: All of them! This visit, with the benefit of more time, we criss-crossed more of the island, enjoying watching the neighborhoods change. Our house sat at the meeting point of San Marco, Cannaregio, and Castello, which I loved as it opened the way to our exploration of Castello, which I don’t think we’d ever visited before. Lovely! Also, our Airbnb host pointed us to the far eastern end of Venice where you can find parks and also Via Garibaldi, the only “Via” in Venice. Wow! A broad and gracious avenue, it feels like classic Italy, but with a Venetian twist. If you’re on Via Garibaldi, I recommend Salvmeria, where we probably had the best cicchetti of our trip, as well as a really divine dish of black polenta with the creamiest baccala.

Favorite Fusion food: Our Airbnb host made several recommendations, and as we learned from our flight to Puglia in September, one should always go where an Airbnb host recommends, rather than endlessly combing through Tripadvisor. Every recommendation was top notch, and when we ran into our host in the street (twice, I’m telling you, Venice in December is just like a big village—we even ran into him at a restaurant), he eagerly asked where we’d eaten and what we thought and if the price was “correct” (for Venice yes, very much so, for Umbria, no…we’re used to our pasta being under €10 a person) and said that it’s really important that he knows how people enjoyed where he sends them—if quality drops off without him knowing, his popularity as a host would also decrease. That, and the fact that we’d been hungering for Asian food for months, prompted us to hustle to Osteria Giorgione di Masa. Honestly, it felt like an embarrassment of riches. We wanted simply everything but contented ourselves with ramen, a bowl of eel over rice, and a Japanese small plate tasting menu, billed as “cicchetti”. Everything was thoughtfully and expertly executed, with varied and nuanced flavors that enchanted my tastebuds (love the bergamot, a popular flavor in Venice, actually). A hearty recommend.

Favorite Market: Obviously, there’s only one answer here, the Rialto Market. Our Airbnb wasn’t equipped enough for actual cooking, but if you are here for more than a few days and your rental boasts at least a strainer and a spatula or wooden spoon, I recommend making the Rialto Market a part of your meal preparation. Even without that, we came here multiple times to admire the millions of kinds of seafood, and also the produce, which explodes with color. Maybe because it’s winter and therefore cold, but the market smelled more of produce than fish. We did pick up a curious kind of vegetable called a “rose”. It seemed to be a cross between radicchio and lettuce, with its earnest blushing color and yielding leaves. We brought it home for a salad with our take out pizza. Wonderful! I also much enjoyed all the kinds of radicchio, which in the Veneto are often cooked. Even if you pick up nothing, just watching Venetians exhibit not one hesitancy about buying a fish you could sling across your back or a handful of shelled creatures you’ve never seen before is worth the visit. The Rialto Market has been a lifeline of fish mongers for almost a a thousand years. Just standing in it and letting the history wash over you is sublime.

Favorite outdoor dining: Our Airbnb host marked a fondamenta in Cannaregio as a “food walk” so you know I insisted we hoof it there as soon as possible. I’m not sure what I expected in a food walk, but what I found was a row of dining establishments with outdoor, canal-side seating. We found an open-table at a likely looking restaurant and discovered it was the exact place a friend of mine recommended, Al Timon. Al Timon bills itself as a wine-bar and restaurant, and since we went twice, we got to experience both. The first time, we ordered the steak and even though our waitress stopped us from ordering anything more, I still was unprepared for the enormous cutting board holding the most enormous sliced steak i’ve ever seen, along with friend potatoes, sauteed greens, and a variety of other vegetables. Unbelievably wonderful, especially with the drifting sunshine and sudden-party atmosphere of men walking their dogs running into women in boots holding a package from the post office and stopping to laugh with other friends before turning to a table to enjoy a glass of wine together. Loving the feeling so much, we went back on our last full day just for spritzes and cicchetti. It’s hard to convey how “neighborhood” this fondamenta feels, we could have gone every day and sampled other places along the “food-walk.”

Favorite Venetian food made by Russians: Al Cantinon was another Airbnb recommendation, and oh, man, did we love it. I particularly loved my dish of black spaghetti with cuttlefish sauce, served on saffron-laced potato cream and topped with red shrimp prepared almost like ceviche. I get that reads like TOO MUCH TOO MUCH, but it was…otherworldly. Soft and decadent and bright and unctuous. Plus, it left an amusing spatter of black drops all around my plate and made my smile the envy of all my family. Who wouldn’t want their mouth to appear cavernous?

Favorite Pizza: As mentioned, Antico Forno, which was so good, it wasn’t just our favorite pizza, it was our only pizza. The pizzeria was right over the light-spangled Rialto Bridge from our apartment, so we could bring it home and have it be piping hot. Also try their craft beer. Win!

Favorite Basic Venetian Fare: For no-frills dining, I recommend my birthday destination of La Colonna. Since we arrived late, after rowing, we were one of only three tables, the other two were filled with what seemed to be carousing fishermen. I loved how their laughter filled the restaurant as much as I loved our simple selections of pasta and seafood. Our cat-loving family particularly enjoyed this little scene: During our meal, we noticed a cat wandering in the (empty) outdoor dining area, never going far. As the fishermen stood to leave, one of them went outside and brought the cat in, to the laughter of the other men. We wondered if this guy just goes around picking up random cats, but then he leaned down and the cat leapt nimbly to the man’s shoulder, where it quickly took up what we could only assume to be his habitual position. His eyelids drowsed as the man took his leave, and we watched in amusement as the opened the door, waved goodbye, and took off down the street, cat tail bobbing behind him.

Favorite warm up: Illy Caffe. This would not have occurred to me, so I’m glad Trisha mentioned it and put in on our map, as it was perfect to warm our cold hands without having to enter a building. Just outside of Piazza San Marco, and set in a garden, we whiled away a pocketful of time perusing what seemed an endless menu of coffee and hot chocolate options, and then exuberantly sipping them while admiring the garden.

Favorite Venetian Cafeteria: Rosticceria Gislon is a rosticceria not a cafeteria, but as many of their food options are prepared and on display, it kind of feels like a cafeteria. I found it tucked away in a covered walkway around the corner from our apartment and then Trisha mentioned it as a local hang out which was enough for me to check it out. It’s the kind of place where men stand behind the counter, old drugstore style, ready to expertly put a bit of this or that onto a plate with a pair of spoons. It’s the kind of place where some people linger over a glass of wine and nibbles from the fried cicchetti bar and some people don’t even take off their coat, and sometimes those are the same people. It’s casual and always crowded. We stopped in for two meals, one of seafoods, both in salad and fried form, and another for roast chicken and potatoes. It was super easy to request this or that added in, like the grilled radicchio and the marinated artichokes. I had to stop myself from exploring their mounds of different kinds of baccala, which I noticed many people enjoying with a wedge of polenta and some marinated fish. This is a great option when you want to dine in a place that time forgot.